The scene unfolds like a horror movie: Maybe your child brings home a note from the school nurse, maybe the telephone rings with the bleak news on the other end. Either way, in an instant your world comes crashing down when you hear your child has lice. Visions of hours spent under a bright lamp picking at bugs and your child becoming the pariah of the 2nd grade fill your mind.

Calm down. There is no reason to panic.

Each year, 6-12 million individuals are treated for head lice. The majority of those treated are between the ages of 3 and 12, but lice can find a home on anyone, any age. While the idea of a nearly microscopic parasitic insect taking up residence on your child’s head is alarming, lice do not present a health risk and do not spread disease.

Dr. Tom Fitzpatrick, M.D., a pediatrician at Kaiser Permanente, says the only physical condition associated with lice occurs when a child who is sensitive to the head lice scratches to the point of developing a localized skin infection.

Actually, the biggest problem with head lice is the persistent myths that surround the issue. The most prevalent myth is that nits— eggs that eventually hatch into lice— are passed from one child to another. According to the National Association of School Nurses, this transmission does not happen. The nits are held to the hair shaft with a glue-like substance and are extremely difficult to remove. According to Dr. Fitzpatrick, even mature lice are not as contagious as the general public believes. More of a concern is the time that infected children spend out of school and parents spend away from their jobs to care for children with head lice.

Lice at School

Many schools are changing their previous “no nit” policy to one of no live lice. In the past, a child with head lice could not return to school until his or her head was free of both lice and nits. The problem with this policy was that a child could easily miss two to three weeks of school for one outbreak. A child who has nits does not have an active case of lice. When the “no nit” policies were in place around the country, up to 24 million school days were lost each year due to the absence of students with nits. Given the documented results of high absentee rates, such as disciplinary problems, failing grades and social difficulties, working to keep children in school is the preferred solution concerning kids and nits.

Treating Lice

According to Dr. Fitzpatrick, the most effective nontoxic treatment for head lice is the application of a one percent permethrin creme rinse. Available over the counter, a popular brand is Nix. Apply the creme after shampooing the hair, and allow the rinse to soak on the head for ten minutes. Once you rinse the treatment, do not apply any other creme rinses or additional products, such as vinegar, to the hair. These products can reduce the effectiveness of the lice treatment.

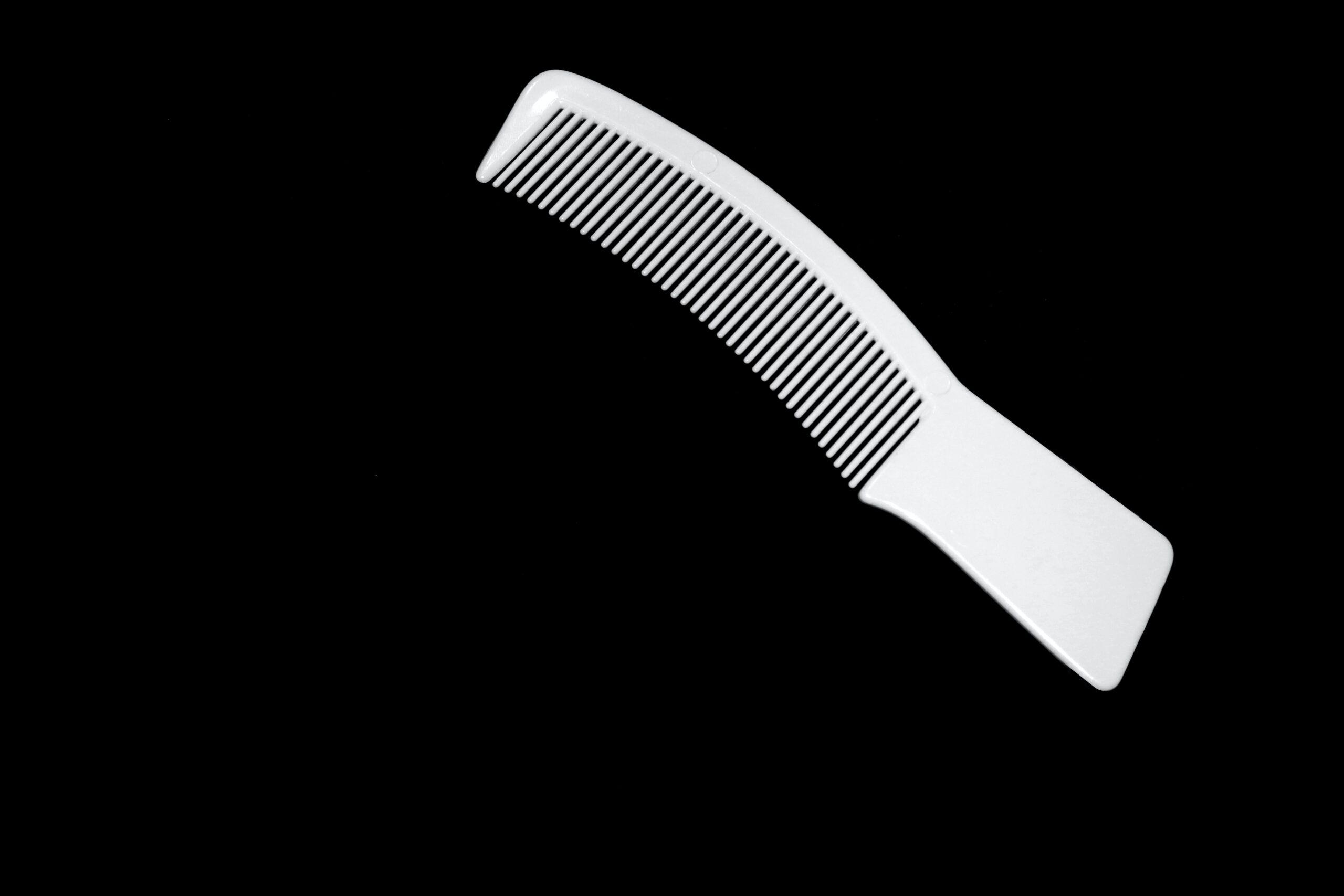

Because permethrin products do not penetrate an unhatched egg, a reapplication of the medication may be needed in seven to ten days. You can also comb the hair with a “nit comb” or even a flea comb, available in the pet section of your local supermarket, every two to three days to remove the dead and dying lice. If after two treatments of over-the-counter medication you continue to wrestle with a lice infestation, your child may have resistant lice. A phone call or visit to your child’s pediatrician can provide you with a prescription for Ovide (Malathion) or Kwell (Lindane). Because these are more potent medications, they are not the first choice for lice treatment and should only be considered when other measures have failed.

Dr. Fitzpatrick realizes that when some parents ask for nontoxic treatments, they intend to inquire about a non-medicinal, natural treatments. “This is tricky, though,” says Dr. Fitzpatrick, “because different people mean different things by natural. For example, permethrin is a synthetic form of another chemical called pyrethrin, which occurs naturally in chrysanthemums— and pyrethrin is effective against lice, too…just not as effective as permethrin, and slightly more toxic to mammals.”

Natural products claiming to be effective against lice are available, says Dr. Fitzpatrick, “but I am cautious with these as natural products; they are not required to meet FDA safety and efficacy standards, which makes them difficult to evaluate. Natural products can still have toxic effects, so I don’t recommend them unless I have seen a study that demonstrates that they are safe and that they work.”

Normally, you can observe lice dying soon after the application of a permethrin-based product. Under the new no-live-lice policies in many school districts, this means children’s immediate return to school. Dr. Fitzpatrick would like to see less concern about the transmission of lice, which are most typically spread through direct, head-to-head contact, and more emphasis placed on keeping children in school.

Given the life cycle of the head louse, once a child is discovered to have head lice, he has probably had them for several weeks. In Dr. Fitzpatrick’s opinion, letting an infested child complete the school day makes sense. The parent can be notified and treat the child that evening, and the student may return to school the following day.

Lice at Home

When your child has lice, washing, plastic-bagging and vacuuming everything in your home is not necessary. Any clothes, bed sheets and machine-washable items your child had contact with within two days of discovering and treating lice should be washed in hot water and dried in a hot dryer. For clothes that cannot be machine washed, dry cleaning works. Stuffed animals too precious to risk time in the washer? Seal them in a plastic bag for two weeks. While there is no evidence that louse eggs will hatch unless they are on a human host, a two-week period is more than enough time to break the louse’s life cycle.

Vacuum your carpets and furniture to remove any stray lice, and your home should be clean. Lice will live less than one day away from a host, so there is no need to drag out every stuffed animal and empty out the closets. By cleaning everything your child was in contact with for the previous 48 hours, you eliminate concerns about re-infestation.

The Facts About a Bug’s Life

Myth: Lice are highly contagious.

Fact: Transmission requires direct, head-to-head contact with a person who has live lice. Lice do not fly or jump; they crawl.

Myth: Sharing a coat closet or locker is a good way to get lice.

Fact: Lice are a parasite and require a host. They feed every few hours, and survive less than one day once they leave their human host. Lice are not anxious to leave their home— the area around the scalp— for a coat or other article of clothing.

Myth: You can smother lice with mayonnaise or olive oil.

Fact: Some parents report success with this method. However, an over-the-counter treatment has a much higher success rate, with much less mess.

Myth: Lice treatments are highly toxic.

Fact: Over-the-counter lice treatments are remarkably safe. Prescription lice treatments, such as Ovid and Kwell, are much stronger and carry an increased risk of side effects.

Myth: Lice can be passed back and forth via the family pet.

Fact: Head lice have only one host, a human, and cannot live on dogs or cats.

Myth: If my child has lice, I should treat the entire family.

Fact: This is unnecessary. Treat only a child with visible live lice.